CVJ October 2023 - One Health: Interprofessional experiences — A bridge to more complete healthcare

September 26, 2023

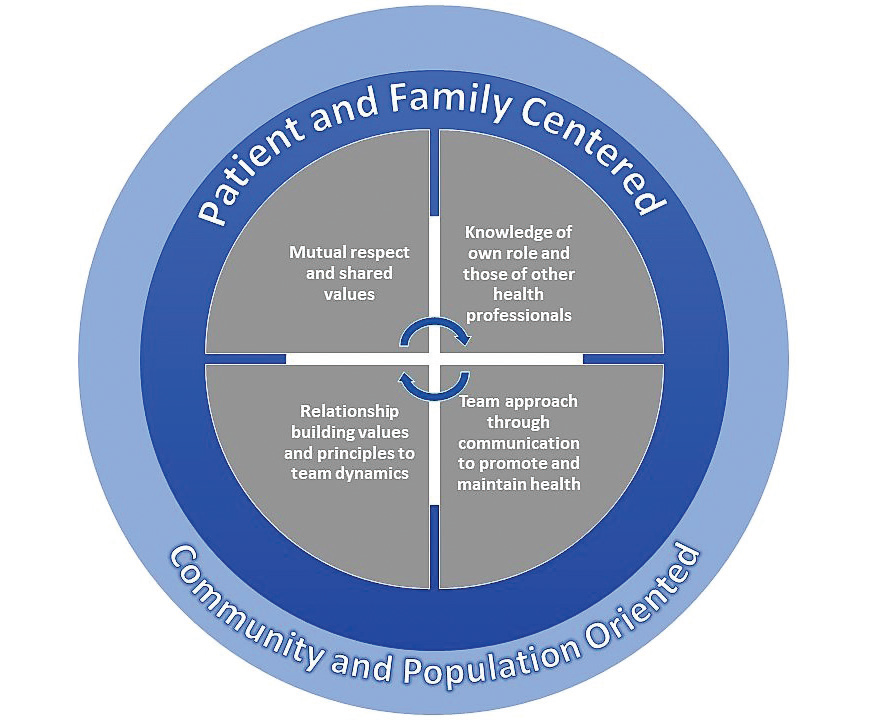

Bringing together different professions to tackle complex health challenges is at the heart of the One Health movement. Interprofessional experiences (IPE) are a codified way of doing this in a formal, educational setting. The Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative defines interprofessional collaboration as a “partnership between a team of health providers and a client in a participatory collaborative and coordinated approach to shared decision making around health and social issues” (1). Building from this, interprofessional education is defined as “members or students of 2 or more professions associated with health or social care, engaged in learning with, from, and about each other” (2). Although interprofessional experiences are required now across public health curricula and many medical school curricula, the uptake has been slow in veterinary curricula and faces many hurdles to implement. Programs that incorporate interprofessional education include dentistry (3), medicine (4), nursing (5), and pharmacy. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) provides 4 core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice in the United States (Figure 1) and includes the professions of osteopathic medicine, pharmacy, physical therapy, dentistry, psychologists, allopathic medicine, veterinary medicine, public health, chiropractic medicine, social work, and nursing (6). Many of these experiences focus on 2 professions interacting (e.g., medicine and veterinary medicine, medical students and nursing students, medical students and social work students, etc.) but few try to bridge 3 or more, thereby limiting their effectiveness in tackling the complex health issues facing society. The benefits of IPE have been documented from improving awareness of One Health, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and ecosystem health. These experiences allow each respective profession to produce more creative and holistic solutions. Additionally, IPEs improve overall communication, team building, and collaboration. COVID-19 has refocused the collective health professions on tackling complex and emergent issues that often fall in the One Health nexus. The ability to draw on the diversity of various health training programs and students through IPEs will drive a better diagnosis, treatment, and outcome for all served by those professions (7).

The challenges of interprofessional experiences seem surmountable given the tangible benefits. However, bringing together cross-disciplinary facilitators and educators often proves to be the biggest hurdle (8). In most institutions, interdisciplinary scholarship may be rewarded but not necessarily teaching; furthermore, curricula across medical, veterinary medical, and public health are vastly different in timing, schedules, and physical locations. Public health programs follow a more traditional graduate degree schedule, whereas medical and veterinary medical schools typically have full days of classes, laboratories, and practical sessions, leaving little time for overlap. Public health programs are generally 2 y, whereas both medical programs are typically 4 y, with very little time for classes in the last year or 2, as they are in clinical rotations. Only 16 universities in the United States have medical, veterinary medical, and public health programs located on the same physical campus. Despite the appetite for these types of experiences, many IPEs stay within 1 sector (e.g., nursing and medical school students or public health and social work) rather than spanning across the One Health spectrum. In a survey of 50 veterinary schools globally in 2020, 20 of the 37 respondents had offerings in some form of IPE, with 9 of those requiring it for all students (8).

At the University of Illinois, we recently implemented a required interprofessional experience across medical, veterinary medical, and public health schools incorporating 250 students and 12 faculty members. This IPE was developed with faculty from all 3 colleges within the University of Illinois, as well as with a community stakeholder, the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District. The scenario incorporated diarrhea in calves and people resulting from contamination of a water well in an unincorporated area from flooding as result of climate change. Students were allocated into groups of 10–12, with at least 1 student represented from each of the 3 colleges participating. Students had 90 min to walk through the case study, respond to prompts as the situation unfolded, and share their expertise while learning about health risks on all sides. This case study was developed over 9 mo with faculty and community partners and built on a successful voluntary IPE among the 3 colleges in the previous year.

As this was the first required IPE at University of Illinois, we did extensive surveying pre- and post-experience. There were statistically significant differences across all questions after the exercise compared to before the exercise (paired Student’s t-tests). The areas considered included infectious causes and risk factors that contribute to diarrhea in human and animal outbreaks, public health initiatives for mitigation of contaminated water sources, consequences of flooding due to extreme weather on animal, human, and community health, strategies to build resilience against future climate threats, and the interprofessional nature of this type of case. Additionally, almost every respondent was interested in additional One Health activities in the future.

As this was the first required IPE at University of Illinois, we did extensive surveying pre- and post-experience. There were statistically significant differences across all questions after the exercise compared to before the exercise (paired Student’s t-tests). The areas considered included infectious causes and risk factors that contribute to diarrhea in human and animal outbreaks, public health initiatives for mitigation of contaminated water sources, consequences of flooding due to extreme weather on animal, human, and community health, strategies to build resilience against future climate threats, and the interprofessional nature of this type of case. Additionally, almost every respondent was interested in additional One Health activities in the future.

The experience at the University of Illinois builds on other efforts to cross these different disciplines (9). Other American universities that have pushed strongly in this area include the University of California-Davis and Ohio State University; the former has followed a formal educational model between medical and veterinary medical schools whereas the latter has sought evidence-based practice opportunities among nursing, veterinary, and social work schools in the community (10). Other examples in use include didactic programs, community-based experience, and interprofessional simulation experiences (1). These are a few examples of ways to approach this ongoing and necessary challenge in education that will help address complex health issues.

Key takeaways for successful IPEs include well-defined learning objectives that could be included in lectures, courses, or curricula. These objectives could range from teaching teamwork to demonstrating an understanding of other health professions to providing a comprehensive foundation on the principles of diseases in the context of sociological systems, global health, and food safety. A key component is ensuring students understand their own professional identity while understanding to a greater extent the role of other professionals in health (1). In addition, IPEs should include outcome evaluations in whatever form that makes sense and will demonstrate short-term impacts. Ideally, outcomes should be measured over a long interval and followed longitudinally to ascertain the true impact on professionals’ ability to work collaboratively throughout their careers (11).

Topics include community health and zoonotic diseases, ethics, preventive health and social determinants of health, patient safety and error reduction, and pharmacy and drugs (8). The underlying best practices include a need for administrative support, an infrastructure well developed for interprofessional activities, committed, and interested faculty, and strong student participation (1).

Interprofessional experiences need to be a mainstay across veterinary curriculums in American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) accredited institutions. The American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC) is a collaborative partner with the IPEC, and IPEs tie directly into 3 of the 90 domains for the AAVMC Competency Based Veterinary Education framework including professionalism, collaboration, and communication. Leveraging the benefits of IPEs in other institutions, the known hurdles can be overcome. With more veterinary programs adopting IPEs, the veterinary profession can look long-term at the added benefits of having collaborative-minded veterinarians who know how to work across the health landscape.

References

- Bridges DR, Davidson RA, Odegard PS, Maki IV, Tomkowiak J. Interprofessional collaboration: Three best practice models of interprofessional Med Educ Online 2011;16:6035.

- Craddock D, O’Halloran C, Borthwick A, McPherson K. Interprofes- sional education in health and social care: Fashion or informed practice? Learn Health Soc Care 2006;5:220–242.

- Contreras OA, Stewart D, Stewart J, Valachovic RW. Interprofessional education and practice — An imperative to optimize and advance oral and overall health. ADEA Office of Policy, Research and Diversity. American Dental Education Association. November 2018. Available from: https://adea.org/policy/publications/ipe/ Last accessed August 18, 2023.

- MedEdPORTAL — The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources [Internet]. Interprofessional education Association of American Medical Colleges [updated 2023]. Available from: https://www.mededportal.org/interprofessional-education Last accessed August 18, 2023.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing [Internet]. Interprofessional education [updated 2023]. Available from: https://www.aacnnursing.org/our-initiatives/education-practice/teaching-resources/interprofessional-education Last accessed August 18, 2023.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative [Internet]. Membership [updated 2022]. Available from: https://Ipecollaborative.org/membership Last accessed August 18, 2023.

- Englar RE, Show-Ridgway A, Noah DL, Appelt E, Kosinski R. Perceptions of the veterinary profession among human health care students before an inter-professional education course at Midwestern J Vet Med Educ 2018;45:423–436.

- Estrada AH, Samper J, Stefanou C, Blue Contemporary challenges for veterinary medical education: Examining the state of inter-professional education in veterinary medicine. J Vet Med Educ 2020;49:71–79.

- Estrada AH, Behar-Horenstein L, Estrada DJ, Black E, Kwiatkowski A, Bzoch A, et al. Incorporating interprofessional education into a veterinary medical J Vet Med Educ 2016;43:275–281.

- Melnyk BM, Dabelko-Schoeny H, Klakos K, Wilkins G, Matusicky M, Millward L, et al. POP care: An interprofessional team-based healthcare model for providing well care to homebound older adults and their J Interprof Educ Prac 2021;25:100474.

- Courtenay M, Conrad P, Wilkes M, La Ragione R, Fitzpatrick N. Interprofessional initiatives between the human health professions and veterinary medical students: A scoping review. J Interprof Care 2014;28: 323–330.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content